SIX MONKEYS: Time Bandits (1981)

Previously: After Michael Palin’s father dies in a Caravaggio painting, he goes to the city and stumbles into the midst of several adventures and a poem. If Gilliam hadn’t already co-directed Holy Grail, this might have killed his career while establishing it…

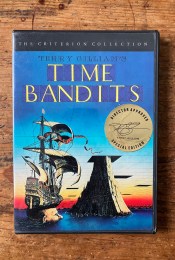

For some reason, I always think that Brazil is Terry Gilliam’s second movie. I’m not sure why. But in my head he has the same narrative as Christopher Nolan: the first film is slight and underseen, basically an amateurish calling card, and then the second one has all the hallmarks that will underscore his auteur status for the rest of his career. And while that remains true regardless of whether Time Bandits or Brazil is his second offering to the movie gods, somehow it’s more impressive if it’s Brazil.

That said, I prefer Time Bandits. Is this in part because I saw it, in whole and in pieces, so many times as a child? Oh, almost certainly. There’s some powerful nostalgia baked into this film in three different ways. Actually, let’s just get into it:

Monkey 1 — Primary Primate: Because, as established in the introductory Six Monkeys post, I watched this so many times over at Geoff’s house, I don’t have a clear memory of watching it for the first time. What I have is a sense of how this movie fits in with other films of the time. In re-watching it, I can see details in the set-dressing of Kevin’s bedroom that helped make it feel real and helped establish the Proustian sensory detail that telescopes me back, Ratatouille-style, to the memories of my own childhood. Kevin’s dun-colored scratchy fake-wool blanket with the shiny polyester trim is absolutely a blanket that existed in my own bedroom, and is what I would swaddle my face in when I had the unaccountable sense that something was moving in the closet in the dark. Did I catch that particular detail when I was watching it in the ’80s? Absolutely not, because it’s almost impossible, as MacLuhan talks about, to see the context of the environment you’re in, and those blankets and those kid fears were too omnipresent to have been seen as a decision and not a default.

Monkey 2 — Infinite Typrewriters: Michael Palin’s diary volume Halfway to Hollywood opens with the extended process of Time Bandits with the first draft being written in a series of scene and story conferences between Palin and Gilliam over the course of January 1980 as a challenge to allow Palin to then concentrate on other work, but the refinement of the script then continues to interrupt his other plans and prevent Gilliam from attending general Python meetings in which the groundwork for what will become Meaning of Life. Palin films with Shelley Duvall in June, is still tweaking dialogue in September for looping, sees an assembly cut in October — “It really is the most exciting piece of filming I have seen in ages” (p.57) — and is editing the script for publication as a tie-in book in December when he hears the news of John Lennon’s death. Time Bandits: the movie script is not by the same publisher as the Holy Grail or Life of Brian script books (they are by Eyre Methuen, whereas this newer offering is from Doubleday Dolphin), but it has a similar vibe, with set photos and Gilliam storyboards collages in amongst the script pages, and a couple section of lavish color plates. While Palin has mentioned “the future scene” his his diaries multiple times (hence the rocketship Wally shows up in), including mentioning the day on which they decided to cut it, it does not appear here as a dangling thread. Maisie and Myrtle, though, cut from the film, are included in their strange The Furies-cum-Circe way, as are photos of their removed scene. Joan Hickson is credited as Myrtle in the final cast list in the book, but whoever played Maisie seems to be lost. The spider-women, as they’re sometimes referred to by Palin and Gilliam, do not appear in the children’s novelization of the film by Charles Alverson, but then again, neither does any of the superlative, hilarious dialogue between Vincent and Pansy about Vincent’s “problem” that has kept them apart, yea these twelve years.

Monkey 3 — See No Evil, Hear No Evil: I have a visceral reaction to the title sequence of this film, both the visuals and the soundtrack. The map feels both organic and precision-tooled, and the soundtrack feels both like outer space and mystical. I know it’s dated, but it is also so of a moment, that I — again, like the set dressing — get telescoped back to what it felt like to be in that era. This should be vertiginous and should reinforce just how yawning of a gap exists between now and then. But it’s so easy for me to land back there that it doesn’t feel like a seven-league leap into nostalgia. I think someone would have to hate that kind of synth sound or have only encountered it retroactively for it to fail to be a gateway. But, yes, I acknowledge that it likely to be many people’s experiences.

The final sequence literally takes place in a castle made of scattered Lego bricks, even though I’m sure they didn’t have the license to show the brand name in the pans across the various toys in Kevin’s bedroom. While I can’t remember even playing with cowboy toys, there’s almost nothing else about fear and fantasy of being trapped in one’s play-acting that doesn’t resonate with me, and I love the fact that this film might be better than even Jacob’s Ladder about creating a situation where, by the end, the audience can’t tell what was real and what wasn’t. I feel sorry for anyone who is left cold by that. Here: wrap yourself up in a blanket.

Monkey 4 — Monkey See, Monkey Don’t: At some point in the drafting of this, I had a solid Thing About Which I Was Dubious to fit in this category. Over the course of actually typing it out, it has faded into irrelevance, or at least been forgotten. I don’t think this is a perfect movie. But I don’t have something that I feel is essential to point at and say, “Oh, goodness, yes: don’t do that. Oof.” Which is saying something about a film that features some pretty amateurish acting on the part of the seven principal roles. The cast are the very definition of traditional Rude Mechanicals. Broadly comic and resolutely clunky — the Belly of the Whale moment where our leaderless band has a crisis of confidence in the direction they’ve been led has no emotional heft at all — they still do what they need to do, which is to advance the action. It doesn’t have grace, but it does have a kind of panache. Am I an apologist? Almost certainly! Maybe I’ll come back and edit this paragraph with genuine criticism if my brain dredges up its original intent.

Monkey 5 — A Barrell Full of Simians: The credits are amazing. Just to start with the alphabetical boldness of John Cleese and Sean Connery, but then we move on to the aforementioned Shelley Duvall, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, Ralph Richardson, and David Warner… Duvall was right off of The Shining when she filmed in 1980, Tron would come the next year for Warner. Holm has been in Alien two years before, and Chariots of Fire came out mere months before this was released. Helmond had wrapped the final season of Soap by the time this was released in the fall of 1981 — Palin writes that the producer of Time Bandits had been relentlessly pursuing Ruth Gordon for the role (who would have been seemingly filming Any Which Way You Can at the same time this was lensing), but Gilliam has been on record many times that Helmond was his first choice. A good record to play, considering how often she continued to show up in his projects. And that’s before we get to the Bandits themselves, which include the chief Jawa, Logray, R2-D2, the chief Ugnaut… many of whom were on both Not the Nine O’Clock News and Spike Milligan’s Q programme. For the past couple weeks, the Kermode and Mayo show has been talking about films that have unexpectedly stacked casts, and I think this very much qualifies.

Monkey 6 — Monkey Business: In Gilliam on Gilliam, Terry talks about how the film was so successful it was the most successful independent film of record until Cleese beat him with A Fish Called Wanda. In The Battle of Brazil, Matthews says that the film cost $4 million to make and made $48 million. It was a film that whole families could go see, and they clearly did. And the reason why I’m quoting The Battle of Brazil is that the success of Time Bandits was one of the reasons why Gilliam ended up working with Universal Pictures, because studios were interested in investing in the Terry Gilliam Business, as — regardless of whether this is actually true — nothing predicts success like success. Except that might not have been the bets choice for a wildly commercial movie studio to invest in an anarchist cartoonist who was a spiritual successor to the creators of Mad Magazine. But that’s jumping ahead to the next entry…

I think it’s pretty clear that I don’t have a lot of critical distance from this one. So on a scale of I Don’t Give A Monkey’s, Monkey In The Middle, or A Great Ape, I will solidly and confidently declare this is A Great Ape!, I think it’s possible to disagree with me. But I would find it difficult to listen seriously to a counter-argument. It ticks so many boxes! And it really feels like the script does everything that Jabberwocky did, but does it well this time ’round: an unchanging, static hero, but this time successfully affecting the characters around them, so that they grow and change; an ironic ending that lands — and lands hard! — successfully and comically undermining a heroic story structure; satire of commercialism that is interwoven throughout, not just feinted at. It doesn’t feel of a piece with Jabberwocky, but structurally Time Bandits is addressing the same major themes and worrying at the same preoccupations, but doing so with stronger comic set-pieces, better gags, and scarier monsters (it is oft-cited that Jo Rowling wanted Gilliam to direct Harry Potter, and has there ever been a clearer line of descendence than the dementors being the offspring of Evil’s tentancle-handed Mari Lwyd beasties?).

Related Links:

+ The TVTropes page contains quite a lot of trivia about casting and production, just divided up in their strange way of putting everything in a cutesy themed category. Not at all like organizing one’s response to a film based on Monkey Idioms, no, of course not!

+ It Came From… also has a good round up of production trivia. Some of this rings bells from having read Gilliam on Gilliam and some from having skipped through the Criterion commentary track.

+ Alice Fraser’s SF/Fantasy podcast Realms Unknown happened to focus on “Narnia” as a trope this week, so I wrote to her about how Time Bandits had its gestation as an image of a horse bursting out of a wardrobe in a reverse-Narnia. Listen to see what other connections were made on that theme.

RSS feed

RSS feed

Leave a comment