SIX MONKEYS: Jabberwocky (1977)

As of this writing, it’s been about half a year since the 50th anniversary of the theatrical release of Monty Python and the Holy Grail and the one-year anniversary of when I last saw Grail‘s co-director Gilliam live on-stage. He showed up, with Michael Palin, to reminisce about the recently deceased Neil Innes for a tribute concert. Palin and Gilliam shared some memories of his contributions to the soundtrack, and then led the audience in a sing-a-long to “Brave Sir Robin”. Palin fulfilled his standard role as “the Nice One”, warming the audience with his traditional, and highly valued, public-facing energy, while Gilliam came across as a bid befuddled. It wasn’t full-on worrisome, but after the deaths of both Jones and Innes, and in the middle of an event where the vast majority of the participants were men approaching full dottering-ness, it did give me pause. During the pre-recorded intro to the 50th anniversary screenings of Holy Grail, Gilliam was in better focused, jolly form, trotting out some vintage anecdotes in fine fettle.

Holy Grail has become a perennial comedy, as much beloved for being beloved, as it is funny. The 50th screening I went to was pretty well attended compared to the shocking emptiness I encounter in most other showings at that cinema. The twenty-eight other people there seemed to be comprised of people who thought they knew the script by heart; people who had fond memories of having seen it back in the day, but didn’t have a home video library; and a few people who wanted to give their kids/girlfriends the Big Screen Experience of a videotape classic. It went over well, but it didn’t have the uproarious lunatic edge I remembered vividly from my first viewing. One guy still lost it at the “A Møøse once bit my sister…” bit, and in general I would say Holy Grail‘s titles do an absolutely superlative job of sweetening an audience for the film to come. It’s an ecstatic combination of subverted expectations and excellently curated stock library music.

Which brings us to Jabberwocky. A difficult row to hoe, adapting one of the most-memorized poems (due in part, certainly, to its adapted use in roughly a bazillion high school chorus concerts). It certainly has the skimmings of a plot, but it’s pretty bare bones. But it is very clearly the follow-up from a director of half of Holy Grail, and it’s mere months away (does about sixteen months count as “mere”?) from having its own fifty-year re-evaluation.

Monkey 1 — Primary Primate: I can’t place exactly when I first saw this film, but I remember finding it crude and not as funny as I would have liked. Parts of it felt like as if Gilliam had taken the set-dressing and world-building from the establishing shots of Grail‘s “I’m Not Dead Yet” sketch and given them feature length. I remember liking the jabberwock itself and finding it to be an excellent adaptation of the Tenniel drawing but with the more lumpy, bulbous aesthetic of the halo of muslin and organics that encircled the Red Knight in The Fisher King, which means I must not have tracked this down on videocassette until some time in 1992 or later.

Monkey 2 — Infinite Typewriters: In Gilliam on Gilliam, Gilliam talks about the slightly accidental way in which Jabberwocky fell together out of wanting to work with Richard Lester and nogotiating other projects with certain producers. In Gilliamesque, he basically repeats what he told interviewer [name here], but with a few more conversational flourishes. The anecdotes about how small and collaborative the production was, and how much was achieved through throwing black cloth over sections of castle or repurposed sets from other films also are pretty much verbatim between the two accounts, which makes me assume Gilliam probably retells the same remembrances on the DVD commentary.

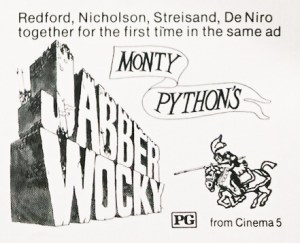

Monkey 3 — See No Evil, Hear No Evil: Upon rewatch, now as a Criterion edition, this looks gorgeous, and some of Gilliam’s medieval preoccupations pay off in a way that they didn’t in washed-out NTSC. The film sets its cap in a visual landscape that evokes Breugel as well as the Dutch masters of chiaroscuro. The lighting and the scene settings really evoke a painterly mise en scène, and the rich blacks of the shadows — especially check out the scene where Palin’s character’s father is on his deathbed — are lush and deep in HD. It really feels deliberate, and not just lighting being used to obscure a lack of sets or set dressing, which would be a logical leap one might take after reading the accounts above. I mentioned the use of stock music in Holy Grail, and Gilliam returns to that well again here, using score excerpts from the DeWolfe library. This includes a music cue during the jabberwock attack that is straight out of Grail: for someone who talks about being frustrated that the film was reviewed almost exclusively through the twin lenses of “an adaptation of the Lewis Carroll poem” and “more from them Python boys” (the latter being something he particularly gets shirty about when advertizers explicitly tried to market the film as “Monty Python’s Jabberwocky”, which was quickly put a stop to), then perhaps Terry should have tried a little harder to create some distance from their recent prominent theatrical outing. And using a beat-for-beat sound-alike moment will only serve to reinforce that overlap.

Monkey 4 — Monkey See, Monkey Don’t: Gilliam talks in the commentary and in the GoG interviews about how he saw the story of the movie as two different kinds of fairy tale smashed together. The first is a traditional dragonslayer hero narrative, and the second is the strange narrative of an unlikely hero pressed into an adventure beyond his ken. He also wanted there to be a throughline about commerce, because he regularly fixates on the character of Dennis being like someone who wants to make their fortune by being a shopkeeper or a functionary. He repeats this like its an archetype, but I have to confess it’s not one with which I am familiar. He sees the comedy in having Dennis be trying to have one kind of quest, but being overtaken by other kind of story, culminating in the tragicomic circumstance of our hero having slain the beast and won the princess, but wishing he could instead be married to the crass, dumpy girl who hates him. And, yes, that is certainly the punchline on which the film ends, but it’s debatable as to whether the joke actually lands.

The main difficulty is the gestured-at theme of the corrosive nature of commerce. We are introduced to Dennis as he fails to assist his father, a cooper who cares about craft and artistry, because he’s more loyal to the sniveling, venal Mr. Fishfinger, who is coming up financial trumps because the city is desperate because of the jabberwock attacks. We are told right at the beginning and later when we meet the merchants who are conferencing with the king, that the threat of the beast is creating fortunes for the few. It’s never explained how, really, though; we are Told, Not Shown. Perhaps more impassioned is the death cry of his father, angry that his son is nothing more than a stock-taker. This is followed up by Dennis creating chaos by attempting to make things more efficient. This jinx-factor creates a couple decent set-pieces, but is disappointingly disconnected from anything that helps his eventual victory over the jabberwock. It’s not due to at attempt at an improvement, it’s not due to him trying to help either of the knights increase their portfolio, it’s just cowardice.

And, while I am loathe to engage in “Save the Cat” screenwriting brain, I did constantly bump up against the fact that Dennis takes almost no action and makes no real decisions. I don’t tend to live or die on the notion that a main character must be active as opposed to reactive — I think there’s a lot of comic meat in a hapless hero who stumbles into circumstances that carry him along the rapids. But Dennis really does just wander from scene to scene and stuff accrues. Sorry to compare it to Python, but Dennis doesn’t really hold a candle to Brian, who is also an over-aged naïf who finds himself in circumstances beyond his control or comprehension. But Brian is often running into a new set of comic stakes; the peril is a valuable motivator that lends the semblance of action to a passive protagonist. Dennis’ stakes don’t really heighten, which is a problem with a script that should be inexorably pushing a character closer and closer to the slavering jaws of doom.

Monkey 5 — A Barrel Full of Simians: Gilliam praises the cast, particularly in contrast to the Pythons, for taking direction and being amenable to circumstance. They made him feel like a real director, and he elevates them to true pro status. That said, they don’t immediately ring out as That Guys, even to a UK comedy watcher like myself. I do apologize to Warren Mitchell, Max Wall, and Brian Pringle. That said, in addition to Terry Jones, Michael Palin, Terry Gilliam, and Neil Innes appearing in the film, the cucked landlord is Brian Bresslaw, whose IMCv is worth exploring, the cuck-er is Harry H. Corbett of Steptoe and Son, and David Prowse does double-duty as both The Black Knight and one of his opponents. (Apparently the film was shot across the lot from Star Wars, and Gilliam has an amusing anecdote about the crews talking about the respective sets)

Monkey 6 — Monkey Business: IMDb has Jabberwocky’s budget at $500,000 and The Numbers has a box-office report of $19,200. I don’t trust those numbers at all, but they don’t instill confidence that the actual ones will be considerably warmer.

So, where do I fall, after this re-experience? On a three point rating scale of I Don’t Give A Monkey’s, Monkey In The Middle, or A Great Ape, this has to be squarely Monkey in the Middle. I can be overly reliant on a final impression of a movie in judging the whole, but here i think It’s both interesting and indicative that Jabberwocky both lands the ending and can’t get the ending to work. It makes its point, but it doesn’t resonate. I really enjoyed re-watching this, as it popped in ways that I didn’t remember on first viewing. It was cleverer, there was more going on, and I was excited by the early establishment of the Art v. Commerce narrative. But then I fell asleep three times while watching it over the course of two days, and I’m still not convinced that when I went back to start over and catch the parts I missed, that I actually saw everything. So I think I’m judging the whole work, but I’m not entirely sure.

NEXT TIME: “That’s what I like! Little things hitting each other!” And several more astonishing cameos and quotable lines in a children’s movie with one of the bleakest endings of cinema history.

Related Links:

+ Slashfilm recommends the movie as a lost classic for Python fans.

RSS feed

RSS feed

Leave a comment