Handwriting

Continuing my recent literary fixation, another post about books. Sorry. But when one finds that one’s studies to be a librarian aren’t as bibliophiliac as one anticipated, this stuff is bound to boil up in other aspects of one’s life.

Continuing my recent literary fixation, another post about books. Sorry. But when one finds that one’s studies to be a librarian aren’t as bibliophiliac as one anticipated, this stuff is bound to boil up in other aspects of one’s life.

The Library of Congress is a vaguely disappointing tourist attraction. When I visited there in 1998 I think I expected to be able to wander through the concentric research desks and check out where Robert Redford sat in Three Days of the Condor. I had forgotten, if I ever knew, that it was not actually an open stack library, nor a national library. However, there was a curious exhibit of assorted works on display in an area open to the public. There was a rather awe-inspiring letter from Edith Wharton, who had the most divine, refined handwriting I had ever seen. I made me despair of my own haphazard scrawl… but it also reminded me that the only D I ever got in school was in fourth grade handwriting, and that such elegant curves were probably a dream I shouldn’t bother to germinate.

However, as compelling as that letter was, I must say that the most amazing thing in the exhibit was a page of original art from Walt Kelly’s “Who Stole The Tarts”, an “Alice in Wonderland meets Joe McCarthy” pastiche from The Pogo Stepmother Goose. It was amazing to see Kelly’s careful penwork, and a surprise to learn that he did his pencils completely in non-photo blue.

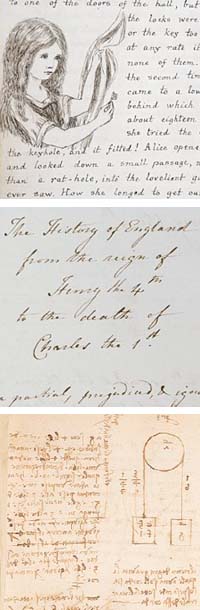

Speaking of Alice’s Adventures, The BBC issued a technology press release today about the addition of the manuscript copy of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground to the British Library’s “Turning the Pages” collection, digital representations of browsable original works that are too valuable and/or fragile to be visited in person. Alice joins thirteen other works, including “the Diamond Sutra, Jane Austen’s History of England, the Leonardo Notebook, the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Mercator Atlas of Europe…” The fact that these are manuscripts and not first editions means that one can attempt to peer into the heart of the writer through his or her handwriting. The samples to the right demonstrate Lewis Carroll’s neat, legible text — almost certainly restrained and refined so that it could be read by Alice Liddell — Jane Austen’s loose student script, and Da Vinci’s famous backwards rebus.

By the way, the above selection of Da Vinci is translated as follows: “.yadretsey aet revo tuoba em gnillet saw sumadartsoN gnuoy taht nworB naD tawt sselkcef siht ekil hcum …seil syawla droc eno no dednepsus ydob a fo ytivarg fo ertnec ehT”

Oxford English-ish Dictionary

I understand that the Oxford English Dictionary does not consider itself to be a prescriptive dictionary. Their mission, to chronicle the important textual usage of words and how that contributes to a wealth of connotation, is a noble one and it provides an invaluable resource. However, the massive undertaking that used to be involved in the updating of a dictionary always made it a prescriptive tool, regardless of its intent. By detailing usage, the OED codified it and validated it, because people treat any dictionary as a usage guide, as opposed to a usage catalogue.

And now that chronicling usage has become simpler, words that are not so much “words” as they are sloppy reductions and adaptations of of established morphemes are being included in the Online Oxford English Dictionary. People worry about the effect instant messaging will have upon communication and upon the writing skills of the current generation of students. Worry more about the student that points with a stylus at the screen of a wireless ThinkPad and says, “Screw ‘formal writing’, granddad… Your precious OED says its a word right there. And if the OED lists it as a word, you can’t mark it wrong on my paper!”

Don’t get me wrong, I think a dictionary should enumerate slang, I just think it should be clearly marked as such. If you’re going to integrate entries, I at least want obvious indications of some sort of verbal caste system.

Usually there’s a minor media kerfuffle about new words included in the dictionary, but updated entries for an online dictionaries — even the OED — must be small potatoes these days when the New York Times (which, I feel I should point out, snooty word freaks would tell one should be properly called the “New York Times“, regardless of what appears on the banner) uses the opening sentence “When you sculpture heads…” instead of “sculpt heads”. Or perhaps I’m off base. Anyway, when the Times can’t be counted upon to fact-check stories, uphold its position as the fifth estate, or even maintain the standardization of the English language, then the following excerpted list shouldn’t seem too surprising:

The following completely new entries were added to OED Online on 9 June 2005:

abdominizer, n.

alley-oop, adv., int., a., and n.

arsey, a.

beered-up, a.

bogart, v.

boyf, n.

brown dwarf, n.

buttlegger, n.

buttlegging, n.

carb, n.2

clip art, n.

conspiracism, n.

co-pay, n.

dagnabbit, int.

deconflict, v.

dequeue, v.

derivatization, n.

derivatize, v.

derivatized, a.

dickwad, n.

disconnect, n.

downwinder, n.

dumpster-dive, v.

emo, n.

emo-core, n.

ergogenic, a.

fabbo, a. (and int.)

filmize, v.

FOAF, n.

foo fighter, n.

fubar, v.

girlf, n.

grammatology, n.

he-said-she-said, a. and n.

in-box, n. and a.

ka-ching, n. and int.

ka-ching, v.

skank, v.

techno-shaman, n.

tricknology, n.

versioning, n.

vidiot, n.

wuss, n.2

wussy, n. and a.

zombied, a.

zombification, n.

zombified, a.

zombify, v.

For a complete list of changes and updates, download this 12-page PDF (120 KB). It’s an interesting list: very British in places, and some of the new entries seem head-scratchingly late in coming. Why has “tikka masala” been absent all this time? Still, I wish that a great many of the brand-new entries had been included as variations and sub-entries instead of being given the full-word status of having their own little respective (and — to make my point again — inadvertantly prescriptive) articles.

Eyes Only

Despite my love of John le Carré novels, I have found that the wider realms of British Espionage haven’t really lit my fire. Recently, even though I had been told that his early spy stuff is generally considered to be the weakest of his output, I tried and failed to slog through Graham Greene’s The Human Factor, which wasn’t bad but wasn’t moving at a sufficient clip to retain my allegiance. But after watching a couple of Michael Caine’s “Harry Palmer” films and recalling that for years I’d been listening to interviews with Hugh Laurie where he sung the praises of Len Deighton, I decided that it was probably time to see why they were popularly considered to be influential and gripping.

And I have not found out. It is my habit to read books that were the source for films I’ve enjoyed. I enjoy being able to not have to pay any attention to the movement of the plot, and concentrate solely on the writing. I already know what’s going to happen — with the obvious exceptions that a film’s fidelity to a novel is loose at best — and so can instead look at the craftmanship, at the tricks of narrative and perception, at the doling out of information. So I decided to begin my Deighton investigation with The Ipcress File. And what surprised me was that while Mr. Caine had played the main character with a curious blandness, with a sloping simplicity that made his performance intriguing and compelling, the same lack of passion, verve, or motive force in the character on the page made him a sheer bore. Watching him play characters one off the other, double deal, and lie lacked the ambling off-handedness of Caine’s portrayal and simply seemed… empty. Without being able to read his motivations, there was no compulsion on the part of this reader to follow him along and eventually discover what his end game was. It seemed too blandly happenstance to actually have an end game in mind.

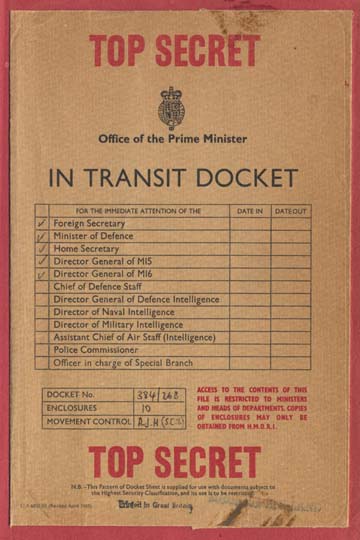

I am about to give Deighton a second try, though, based not upon my hopes for his writitng or the clever plots detailed on the cover blurbs. No, but because of a clever piece of gimickry discovered in a vintage copy of An Expensive Place to Die, the first American edition, as printed in 1967. On the inside front flap there is a TOP SECRET document folder, containing miniature facsimilies of fictional memoranda of documents apprently key to the story events contained within.

Verisimilitude, or attempts thereunto, will almost always pique my interest. And so I am giving Len Deighton a second shot. For those interested, I have made a 1 MB .PDF scan of the dossier available for download. Perhaps it will intrigue you sufficiently as well.

Lastly, the docket folder claims that there are ten items enclosed, but my public library edition only has three documents remaining. Anyone with copies of the other seven pages, should they actually exist, is encouraged to share them with me.

RSS feed

RSS feed